Research

Research to Improve Indigenous Health

Indigenous peoples have long faced disproportionate risks from epidemic diseases and precarious health conditions. COVID-19 was no exception (Simionatto, Barbosa, and Marchioro 2020).

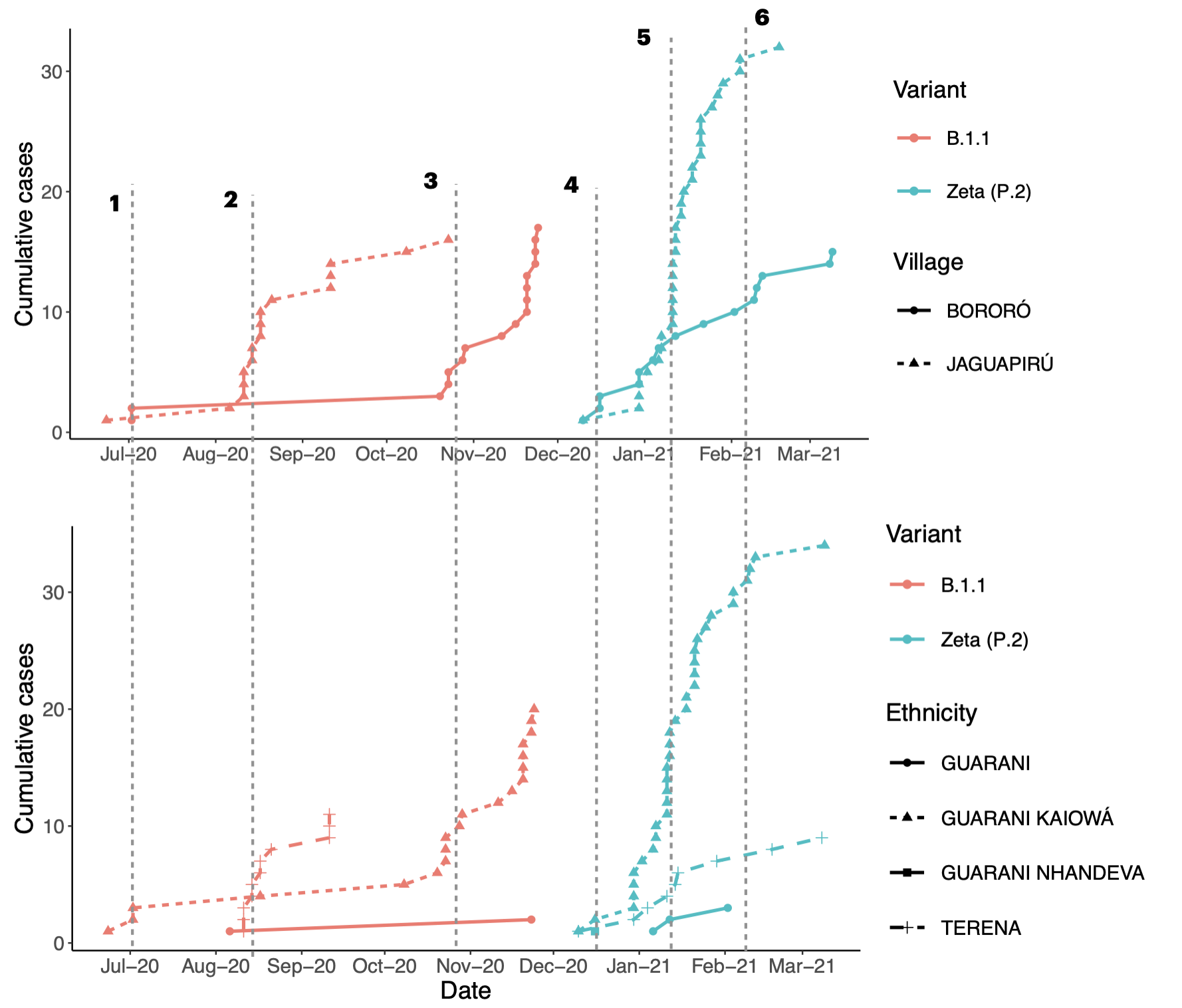

Projeto Dourados continues our collaboration that started when Albuquerque, Rezende, and Simionatto—together with other co-authors—tracked the spread of different SARS-CoV-2 variants within the Dourados Indigenous Reserve (Oliveira et al. 2023).

Our current research builds on their work by using original data to explain how social structure shaped transmission in the Reserve during COVID-19. Social structure means who interacts with whom, and how often. Geography shapes social structure: we interact more often with those nearby than far away. Cultural, ethnic, and economic groupings also shape these patterns.

The goal of this research is to support residents of the Dourados Indigenous Reserve in preparing for future pandemics. We develop computational tools that allow different response strategies to be explored through simulation, making it possible to anticipate trade-offs before crises arise.

While grounded in the context of Dourados, we intend our work to be adaptable to improve preparedness and disease prevention in other Indigenous communities in Brazil and beyond.

The Dourados Indigenous Reserve

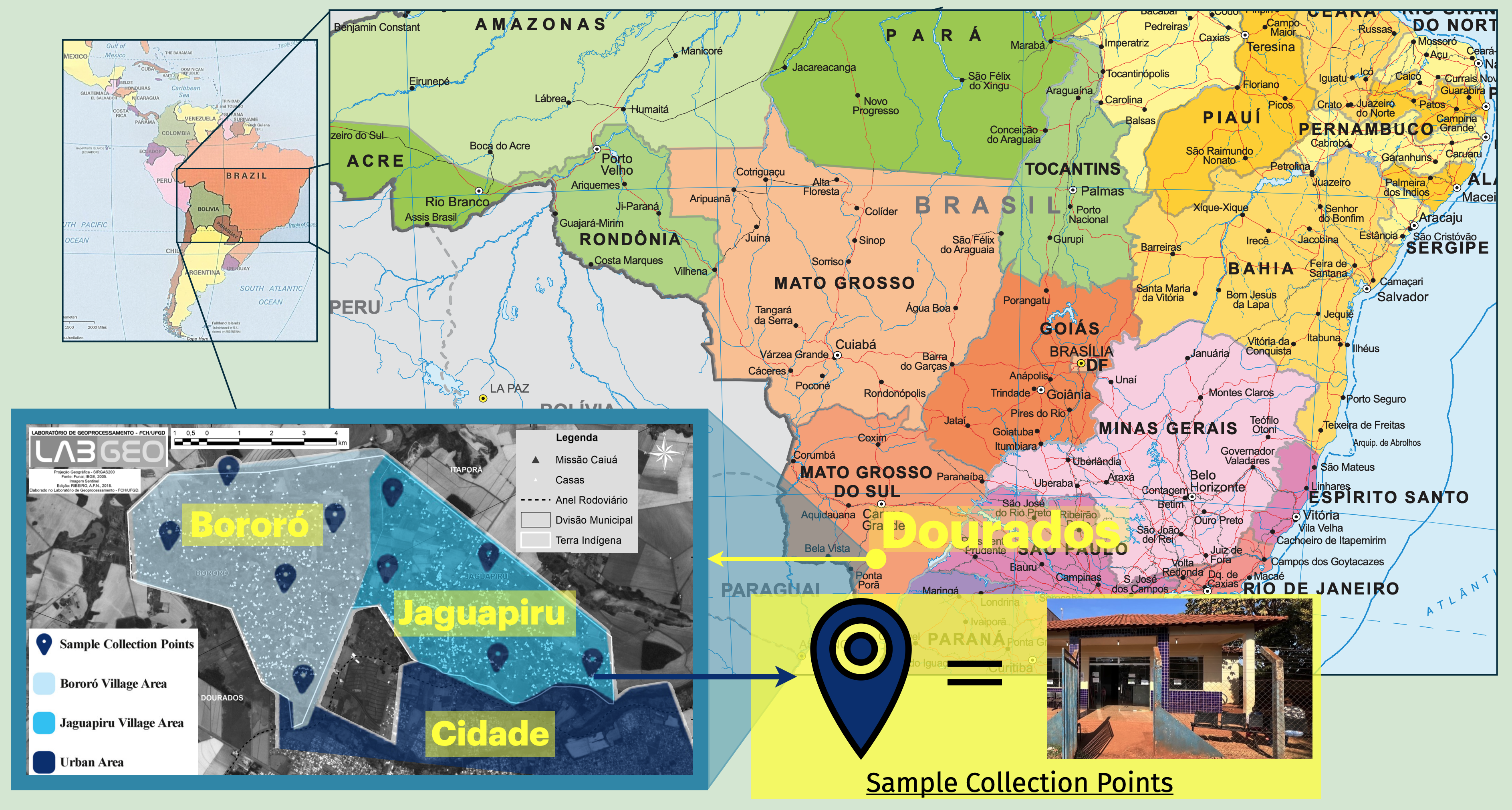

The Dourados Indigenous Reserve is located in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul, in southwestern Brazil, adjacent to the city of Dourados (Figure 1). The Reserve lies within a region shaped by long histories of Indigenous settlement, displacement, and state-led reservation policies, which brought together multiple Indigenous groups into a shared territory.

Today, the Reserve is home to approximately 18,000 residents living in two villages: Bororó and Jaguapiru. Jaguapiru is the larger of the two, with roughly twice the population of Bororó. The population includes members of multiple Indigenous groups, with Guarani Kaiowa and Terena comprising the largest shares of residents.

The spatial organization of the Reserve reflects its proximity to the city of Dourados while remaining socially and administratively distinct. Figure 1 situates the Reserve within Brazil and shows the relative locations of Bororó and Jaguapiru, along with sites used for public health surveillance during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Daily life in the Reserve is supported by a mix of shared institutions and local infrastructure (Figure 2). The Reserve’s hospital serves as a central hub for care and includes both a Christian chapel and an outdoor ceremonial structure with a fire pit used for Indigenous spiritual practices. Smaller public health stations and independent storefronts provide essential services throughout the Reserve.

Current Research Project

Turner is leading an effort to formalize the hypotheses above into an epidemiological simulation and statistical model of COVID-19 transmission in the Reserve. The goal is to support public health planning for interventions such as incentivizing staying home, so that residents do not feel economically compelled to travel during outbreaks.

We begin by using data gathered by Albuquerque, Rezende, and Simionatto to fit the simulation model using statistical inference. In practice, this means identifying which model configurations generate simulated data that most closely match observed epidemiological patterns.

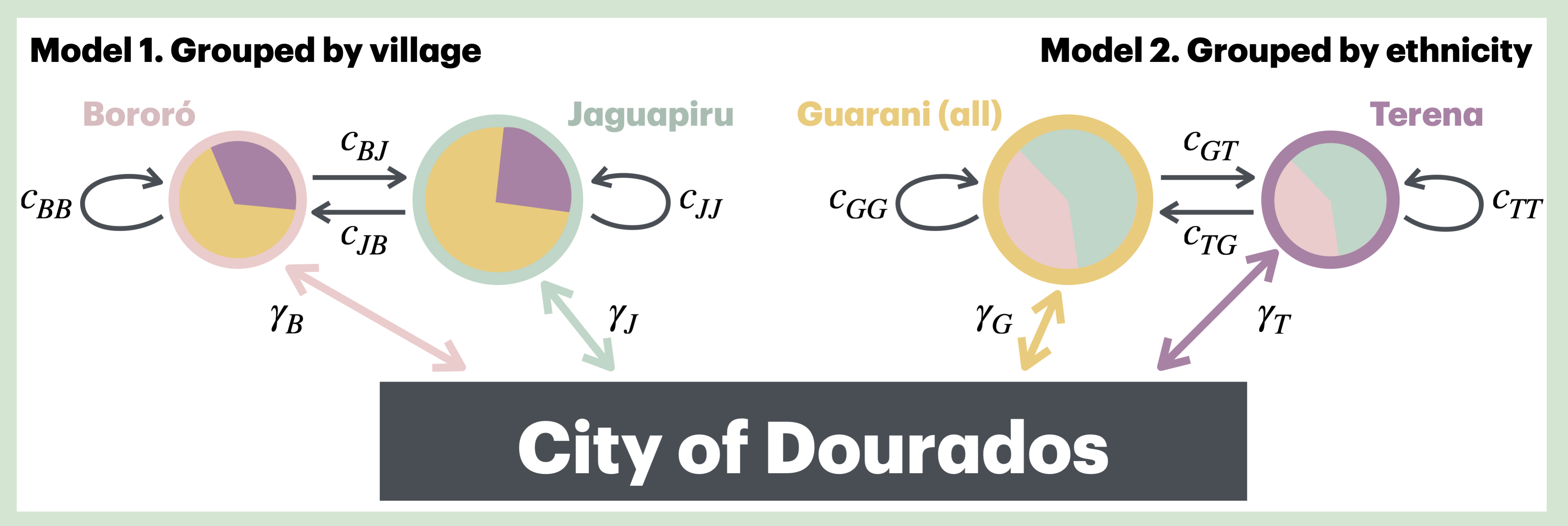

The model represents disease transmission through travel between the Reserve and the city of Dourados, followed by local spread shaped by interpersonal contact networks. A schematic overview of this structure is shown in Figure 4, where mobility and contact behaviors for different social groups are represented symbolically.

To determine which version of this model most faithfully represents COVID-19 in the Reserve, we infer the following:

- Which social groupings (village, ethnicity, or village × ethnicity) produce models that best match the observed data?

- Was travel to the city a significant factor in importing different variants?

- Did reinfection play a significant role in the Zeta outbreak in the Reserve?

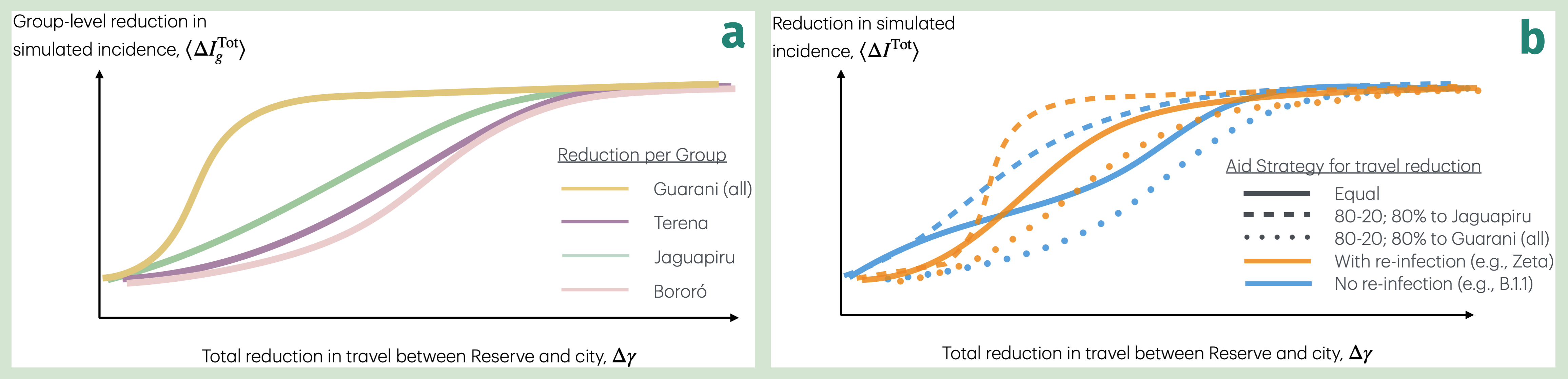

While understanding these dynamics is valuable in its own right, our primary aim is to use this knowledge to prepare effective social interventions before outbreaks escalate. Once a faithful model has been inferred, it can be put to work evaluating intervention strategies.

We use the model to infer which intervention strategies most effectively limit the number of cases under constrained resources. Different strategies correspond to different expenditures aimed at producing specific social changes. In the model, these changes are represented as adjustments to parameters governing mobility and social contact structure.

For example, public funds might be used to reduce travel to the city for one, several, or all social groups. Resources need not be allocated evenly. Given Jaguapiru’s proximity to the city, one might plausibly expect residents of Jaguapiru to travel more frequently than those in Bororó.

Long-term Vision

Efficiency is essential: resources are limited, and we do not have the time or capacity to experiment freely in the real world.

Statistical and simulation studies are valuable not only because they help us understand and predict real-world phenomena, but also because they highlight gaps in our knowledge. These gaps can point to where additional basic research—such as anthropological or ethnographic work—would be most valuable.

We see a unique opportunity to advance public health for Indigenous communities. Our long-term vision includes building a vibrant team of faculty and student researchers working on the ground in Dourados, documenting the Reserve and the public health efforts taking place there. This on-the-ground engagement is essential for grounding the development of effective computational tools for public health policy.